The Racist History of Policing & Prisons in America

- Aug 24, 2020

- 16 min read

Updated: May 2, 2021

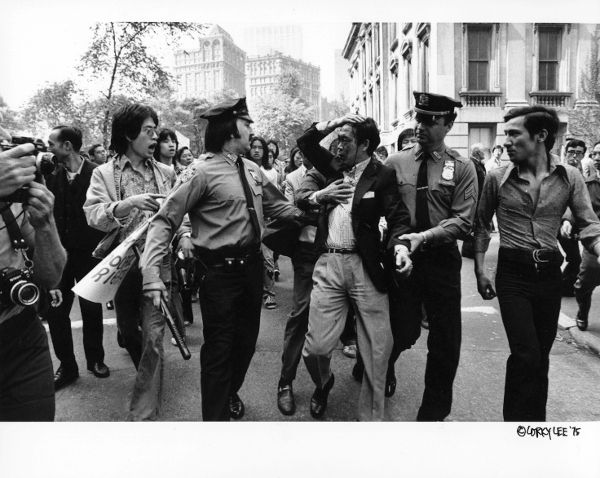

Police restrain a Chinese American protestor calling for the end of police brutality and justice for Peter Yew in a photo by Corky Lee. (source)

“We will fight to the end until all our demands are satisfied. We are angry because we are opposed and discriminated against.”

Man Bun Lee, the president of the Chinese Consolidated Benevolent Association, spoke these words in 1975 amidst one of the largest Chinese American protests in U.S. history. The demonstrations erupted in Manhattan’s Chinatown after police violently beat 27-year-old Chinese American Peter Yew. The officers were tasked with dispersing a crowd after a traffic accident. Yew was a part of the crowd and opposed the way that police were handling the situation. Arresting Yew on exaggerated claims of resistance to and assault of police, the officers beat him. They then dragged him to the local police station, stripped him, and beat him again. In response, thousands of Chinese American protestors took to the streets of Chinatown to demand justice for Yew and an end to police brutality. The pressure from protestors ultimately led to a reinvestigation of the case, and the charges against Yew were dropped.

The police brutality against Yew is part of a centuries-long history of law enforcement unjustly treating communities of color, including us Chinese Americans. The Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882 barred Chinese immigrants from naturalization and banned immigration from China for 10 years. Congress under President Chester A. Arthur passed the act to assuage white workers on the West Coast, who blamed economic problems and lower wages on Chinese immigrant workers. Those who disobeyed the act were subject to imprisonment and deportation, and a later extension of the act required carrying official residence certificates at all times. Punishment for failing to do so included hard labor, with bail as an option only if they had a “credible white witness” to vouch for them. Even after the Chinese Exclusion Act was repealed in 1943, police continued to harass Asian Americans during sweeps for undocumented immigrants, often commanding anyone who looked Asian to show their resident papers.

In the aftermath of Vincent Chin’s murder by two white men, Asian and non-Asian Americans alike protest together against the unjust criminal justice system in another photo by Corky Lee. (source)

Later, in 1982, Chinese Americans protested against the inequitable U.S. criminal justice system once again after the death of 27-year-old Chinese American Vincent Chin. When Chin visited a Detroit strip club on the eve of his wedding, two white auto workers, Michael Nitz and Ronald Ebens, beat Chin to death because they thought he was Japanese. At the time, U.S. auto workers blamed loss of jobs on Japanese vehicle manufacturers. Neither Ebens nor Nitz were sentenced to any time in prison; they merely had to pay some fines and face 3 years of probation. Enraged by the light sentence, Asian Americans, such as the American Citizens for Justice, and non-Asian American allies alike protested. As a result of their activism, the U.S. District Court reinvestigated the case in 1984 and ruled that Ebens had indeed violated Chin’s civil rights. “It was the first time Asian Americans were protected in a federal civil rights prosecution,” according to Renee Tajima-Peña, a UCLA professor and co-director of the documentary Who Killed Vincent Chin?

The above instances involving Chinese Americans are not isolated examples of flaws, but rather part of a systemically inequitable U.S. criminal justice system that mistreats communities of color, especially Black Americans. What the Chinese American community felt in these moments was rage—the same rage that compounds for Black Americans each time a Black life is taken or violated by law enforcement.

During the summer of 2020, the murder of George Floyd by police reignited national conversation about criminal justice reform. It has again brought issues of police brutality and unequal treatment of Black Americans by law enforcement to the forefront of public consciousness. As protests spread throughout the country calling for change from lawmakers and police departments, Chinese Americans must understand that injustices of the U.S. criminal justice system that disproportionately affect Black lives—including, but by no means limited to, George Floyd—are symptoms of a flawed, racist system as a whole, and these defects in the form of brutality, discrimination, and corruption impact non-white Americans, including us Chinese Americans.

The U.S. criminal justice system has a long history of violence and discrimination against communities of color, especially Black Americans. Recognizing this unjust history of law enforcement, court processes, and corrections is the first step to understanding how the current system can—and must—change.

Colonial America (Before 1781)

One of the earliest police forces was the Boston Watch, established in 1636. This neighborhood night watch group was tasked with various social service jobs, such as locating lost children, capturing runaway criminals, and putting out fires. Similar night watches emerged throughout the colonies, which were all small and insular at the time, so each community was put in charge of looking after itself. Night watches were composed of volunteers, largely white men who joined to escape military service, forced conscription, or punishment. Augmenting the night watch system were constables, official local law enforcement officers who were also ordinary citizens. They mostly served during the day and sometimes supervised the night watch volunteers.

In the colonial era, people who defied the law were subject to public corporal punishment. Besides instituting fines, law enforcement also whipped, mutilated, and branded offenders. Being sent to the stocks was a way of restraining criminals as well as publicly humiliating them. In extreme cases, exile from the community and the death penalty were instituted. At the time, incarceration was not used as punishment; jails simply held prisoners between each court session. The local magistrate, a political or religious leader but not a professional judge, decided the verdict for court cases concerning minor crimes.

Post-Revolutionary War (1781-1865)

After the Revolutionary war, the new codified U.S. laws replaced the king’s authority. The independent colonies transformed from small, insular communities into rapidly growing cities with diverse communities. Due to the population growth and new social mobility during this time, white Americans believed that neighborhood night watches and corporal punishment were not enough anymore. As a result, the penitentiary system emerged.

The use of prisons replaced public punishment to reform criminals. The conversion of the Philadelphia Walnut Street Jail into a state prison in 1790 is the earliest example of convict confinement in the U.S. Prohibited from interacting with each other, criminals imprisoned in isolated cells. Starting in the 1820s, solitary confinement was accompanied by hard labor. This first occurred at the New York Auburn prison system, where prisoners congregated to work in forced silence during the day and separated to continue working at night.

Around the same time, centralized police forces in America were also created in response to rapid urbanization. In the North, states modeled their police forces after the British version. Boston created its first police force in 1838, followed closely by other major American cities. Codified laws were put in place for police who served as full-time employees reporting to a bureaucratic central government authority.

In the South, a police force completely different from that in the North was established. White Southerners wanted to use law enforcement to control enslaved African Americans, so they created slave patrols. Starting in 1704, these slave patrols punished enslaved African Americans who were traveling without permits or disobeyed “slave codes,” laws specifically designed also to control the Black population. Additionally, the Fugitive Slave Acts enabled slave patrols to capture and return enslaved African Americans who ran away to their slave owners. These laws show that, from the beginning, the U.S. criminal justice system maintained systemic racism by criminalizing Black Americans while serving only the interest of white Americans.

Post-Civil War Era (1865-1968)

Although the 13th Amendment—passed at the end of the U.S. Civil War—officially abolished slavery, a loophole in the law—known as the Black codes—made it possible to enslave Black Americans as punishment for crimes. Harvard professor Khalil Gibran Muhammad explained in his book The Condemnation Of Blackness: Race, Crime, And The Making Of Modern Urban America: “The Black codes, for all intents and purposes, criminalized every form of African American freedom and mobility, political power, economic power, except the one thing it didn't criminalize was the right to work for a white man on a white man's terms.” These laws enabled white Americans to continue exploiting Black Americans for their labor as long as they were imprisoned, even after slavery was technically outlawed. With an economic incentive to arrest and imprison Black Americans for cheap labor, police frequently arrested Black Americans for minor offenses or vagrancy. Since most Black Americans were just recently liberated from generations of working for free as enslaved laborers, they largely could not afford to pay the fine for these minor offenses or vagrancy. As a result, Black Americans made up the overwhelming majority of the prison population and were forced into labor contracts.

From 1846 until 1928, both Northern and Southern state governments leased Black convicts as a cheap labor force to private companies and businessmen. This convict leasing system was essentially slavery by another name. It made tremendous profits for both the state and white entrepreneurs, but at the expense of exploitative working conditions for Black prisoners. Eventually, chain gangs of Black convicts—shackled together at the ankles so that they would not escape—were developed to perform brutal labor like digging ditches, farming, and constructing roads. Convict leasing was more pervasive in the South, where states leased Black convicts to work for local planters and to repair Southern society, much of which was destroyed by the war. However, many Northern states also leased Black convicts to manufacturing companies. In her book Are Prisons Obsolete?, activist and UC Santa Cruz professor Angela Davis notes that many believed convict leasing was, in fact, worse than slavery, because the prison administration had no incentive not to work Black convicts to death, as prisons would save money with less prisoners to care for.

From the post-Civil War era to the 1960s, Jim Crow laws legalized segregation and further targeted communities of color, especially Black Americans, at the hands of law enforcement. In both the North and the South, these laws denied non-white Americans the right to education, hold jobs, vote, and a host of other opportunities, making them second-class citizens. Refusal to obey Jim Crow laws was met with fines, arrest, jail sentences, violence, and even death. Additionally at the time, white supremacy groups—most famously, the Ku Klux Klan (KKK), who are still active today—carried out campaigns of terror and violence against Black Americans and other communities of color, all while the U.S. police, government, and legal system all turned a blind eye. Many police officers and prison employees were even members of the KKK themselves. Once again, law enforcement and criminal justice not only failed to protect Black Americans and other non-white Americans, but worked in tandem to endorse their death and oppression.

Contrary to popular belief, it was not just the South that had Jim Crow laws; the North also had Jim Crow laws. In fact, Jim Crow laws actually originated in the North before the Civil War. Like in the South, northern neighborhoods and schools were segregated, businesses put up “Whites Only” signs, and landlordss refused to sell or rent homes to non-white Americans. Racism in the U.S. is too often characterized “as a regional problem, not a national problem,” as stated by writer and Brooklyn College professor Jeanne Theoharis.

More centralized police forces emerged across the U.S. in the late 19th century, maintaining the social order between new waves of white European immigrants and freed Black Americans. At the time, local politics and police departments were deeply intertwined. The police would encourage voters to elect politicians, and in return politicians would employ the officers. Politicians also chose the chiefs of police agencies, and the police department had to give a portion of their salary to the dominant political party. Rather than hiring the most qualified officers, local government officials hired officers that would help retain their power in office. Due to the widespread labor unrest during the same period, police were also tasked with breaking strikes by labor unions demanding fair working conditions and wages. Strike-breaking took two forms: using extreme violence to disperse workers, and arresting protestors arbitrarily using ambiguous vagrancy laws. Thus, the rich used the police as a tool for their own economic interests against demonstrating workers.

The overwhelming presence of politics in policing led to rampant corruption. Police protected the vice operations of their political patrons, traded immunity for information and bribes, used peremptory force, and even drank while on patrol. By allying with the police, political machines in big cities created organized gangs that ran gambling, prostitution, and drug distribution.

The Lexow Commission was created in 1894 to investigate police corruption and brutality in New York. The inquiry, created by then State Senator Clarence Lexow, found that police not only harassed citizens, but also profited off of allowing gambling and prostitution to occur. Third degree violence, which is defined as getting information from suspects through infliction of suffering, was a common method used by police to coerce information or confessions out of perpetrators. In Philadelphia around the same time, grand juries similarly exposed police involvement in prostitution and gambling enterprises. However, even after these investigations, police corruption did not stop.

20th Century

During the Prohibition era beginning in 1920, police collaborated with mobsters and condoned illegal smuggling of alcohol, speakeasies, and bootleggers. The Wickersham Commission of 1929, signed by President Herbert Hoover, attempted to undo the intimate relationship between police and politics by making police precincts independent of political wards. Thus began the movement for police professionalization: educated police officers were recruited, and better training centers were established. The technology used by police expanded greatly too, as radio became the primary mode of communication and cars were given to police officers.

Much of the 1960s was defined by the protests of both the Civil Rights Movement and anti-Vietnam War campaigns. Often, police officers used brutality to respond to protestors. Aggressive dispersion tactics such as police dogs and fire hoses were used to disperse protestors. In order to understand the cause of protests, Democratic president Lyndon B. Johnson created the Kerner Commission in 1968. The Commission found that the underlying reason behind the protests was the frustration of Black Americans at segregation codified by Jim Crow laws as well as failed housing, social services, and education policies by federal and state governments. The report strongly criticized white racism in America, and warned: "Our nation is moving toward two societies, one Black, one white—separate and unequal." However, the Johnson administration largely rejected the suggestions for reform.

In 1963, police officers and their dogs attacked a peaceful 17-year-old civil rights demonstrator. (source)

Another key component of Democratic President Johnson’s legacy is the “War on Crime,” which he declared in 1964 as another effort at criminal justice reform. First, Congress passed the Law Enforcement Assistance Act in 1965 (LEAA) to allow the federal government to play a direct role in state prisons, local court systems, and police operations. Then, law enforcement militarized, as the Johnson administration created an agency within the Department of Justice to give grants to local governments for larger weapons arsenals usually only accessible to the U.S. army. The agency had $30 million dollars to purchase military-grade weaponry for local police departments. Another component of the War on Crime campaign was the Omnibus Crime Control and Safe Streets Act of 1968, which made federal grants for riot control and militarization of policing a permanent part of the LEAA. In general, Johnson’s War on Crime policies focused on militarizing policing instead of social welfare programs in a (failed) attempt to curb crime.

The War on Crime was then followed by the War on Drugs declared by Republican president Richard Nixon in 1971. Controlling drugs became a tactic for controlling crime under the Nixon administration, so federal drug control agencies increased immensely in size during this time. Draconian drug laws were instituted, and the number of people arrested for drug offenses skyrocketed. From 1980 to 1997, the number of people incarcerated for drug offenses went from almost 50,000 to over 400,000. Mandatory minimum sentencing and no-knock warrants were also put in place. Rockefeller drug laws enacted in New York in 1973 made the mandatory minimum sentence for those caught with drugs, even the smallest amount and the most minor drugs, to be 15 years.

These policies disproportionately drove up racial profiling and incarceration rates for Black Americans. President Nixon’s domestic policy advisor, John Ehrlichman, confessed: “We knew we couldn’t make it illegal to be either against the [Vietnam] war or Black, but by getting the public to associate the hippies with marijuana and Black Americans with heroin, and then criminalizing both heavily, we could disrupt those communities. We could arrest their leaders, raid their homes, break up their meetings, and vilify them night after night on the evening news. Did we know we were lying about the drugs? Of course we did.” Drug laws and unequal treatment of Black Americans by law enforcement—as enabled by both Republican and Democratic politicians—only became more rampant in the late 20th century.

In 1982, Republican president Ronald Reagan escalated the War on Drugs, supposedly in response to the crack cocaine crisis in Black communities, but this escalation was announced well before crack cocaine arrived in most inner city neighborhoods, where Black Americans largely resided. The Reagan administration instituted zero tolerance policies, which consist of “stopping, questioning, and frisking pedestrians or drivers considered to be acting suspiciously and then arresting them for offenses when possible, typically for such low-level offenses as possessing marijuana.” The Wars on Crimes and Drugs were not only a Republican strategy, but rather a bipartisan effort in which Democrats were also actively involved. Democratic presidents Johnson and Clinton both enacted these racist campaigns alongside Republican presidents Nixon and Reagan. Initially, Bill Clinton advocated for rehabilitation during his presidential campaign of 1992, but when in office, he heavily relied on the same draconian drug war tactics used by the Nixon administration.

21st Century

Due to the legacies of the Wars on Crimes and Drugs, communities of color, especially Black Americans, face even more unequal treatment from the criminal justice system during the 21st century. Overall, while statistics show similar rates of drug use amongst white Americans and Black Americans, drug use is much more heavily punished for Black Americans. In fact, Black Americans are imprisoned at almost six times the rate of white Americans, even though Black Americans represent just 12.5% of illicit drug users. The ACLU found in 2010 that for marijuana possession, Black Americans were 3.7 times more likely to face arrest, even though Black Americans and white Americans use marijuana at similar rates. Additionally, crack and powder cocaine have the same chemical makeup, but there is an 18:1 ratio for the amount of crack cocaine and powder cocaine required to trigger federal criminal penalties. As a result, predominantly white powder cocaine users experience much less punitive measures—if they get punished at all—than largely Black and Latinx American crack users.

The War on Drugs has also led to a major prison boom. Over the last 40 years, the number of incarcerated people has increased by 500% to the staggering 2.2 million people currently imprisoned in the U.S. The prison boom has led to the growth of the prison-industrial complex, which describes how the current U.S. criminal justice system involves the government and private corporations profiting off of imprisonment, policing, and surveillance. This phenomenon is exemplified by the recent increase in private prisons and their profits. The Corrections Corporation of America, which manages private detention centers and prisons, saw its revenues increase from $293 million to $462 million between 1996 and 1997. Like the convict leasing system, private prisons profit off of cheap labor provided by inmates, who are disproportionately non-white. The government or companies that hire convicts not only pay them way below minimum wage, but they also don’t have to provide convicts with insurance and healthcare, as they do for non-incarcerated employees. Major corporations—including but not limited to IBM, Motorola, Honeywell, IBM, and Nordstrom—are still using prison labor today.

The Justice Policy Institute has reported on how prison corporations use campaign contributions, lobbyists, and policymaker relationships for political gain. In terms of spending, budgets for corrections and policing have skyrocketed. Indeed, in 1985, the total state expenditure on corrections was 6.7 billion. Since then, this number has risen tremendously to 59.8 billion in 2017, according to the National Association of State Budget Officers. From 1977 to 2017, state and local governments spending on police forces jumped from $42 billion to $115 billion. According to a 2016 report by the U.S. Department of Education, this increase in expenditure on corrections has increased three times the rate as spending on elementary and secondary education during the same period, demonstrating the government’s emphasis on criminalization over social services. At the postsecondary level, spending on corrections increased by nearly 90% while spending on higher education stayed flat.

In addition, the criminal justice system has become even more militarized after the Defense Department’s 1033 program was created under Republican president George H.W. Bush. The program provides surplus equipment from the military to over 8,000 domestic law enforcement agencies. This equipment includes items such as grenade launchers and armored vehicles, and the cost of equipment totals to more than $7 million.

The Department of Justice also has a program called the Edward Byrne Memorial Justice Assistance Grant program, which provides general funding for law enforcement, courts, crime prevention and education, drug treatment, community corrections, and crime victim/witness programs. However, grantees predominantly use funding for the purchase of military-grade weapons, body armor, and tactical vests. These spending habits reveal the tendency of law enforcement to militarize as well as focus on punishment instead of rehabilitation.

Racial profiling of non-white Americans, especially Black Americans, is also rampant in law enforcement. According to the ACLU, racial profiling is the “discriminatory practice by law enforcement officials of targeting individuals for suspicion of crime based on the individual’s race, ethnicity, religion or national origin.” Besides being stopped at disproportionately high rates, Black Americans are also arrested and prosecuted at higher rates. According to a study of NYPD stop-and-frisk data from 2014 to 2017, although young Black and Latinx men comprise just 5% of the city’s population, they were stopped in 38% of the cases yet innocent 80% of the time.

Using statistics by the Bureau of Justice, this analysis found that police officers are twice as likely to use force against non-white Americans. (source)

Racial profiling has far-reaching consequences outside of police stops, contributing to Black Americans being arrested and prosecuted at higher rates. For example, studies of San Francisco in 2018 have found that 41% of those arrested, 38% of prosecutor-filed cases, and 43% of those booked into jail were Black, even though they represent merely 6% of the population of San Francisco. After arrest, due to racial discrimination, Black Americans are more likely to be denied bail and are faced with higher bail amounts than white Americans. As a result, disproportionate numbers of Black Americans cannot afford bail, so they remain incarcerated for months and up to years as they wait for trial. On the other hand, white Americans who are accused of the same crime are largely able to get out of jail and go home by paying bail.

Furthermore, Black Americans are more likely to be charged with heavier sentences by prosecutors. A 2017 survey from the U.S. Sentencing Commission found that Black men are given sentences 20% longer than those of white men, even when committing the exact same crime. This unequal treatment is present in capital punishment as well. The likelihood of facing capital punishment for a Black defendant is four times higher than that for a white defendant. One reason for these disparities is that prosecutors are charging Black defendants under federal death penalty law much more often than white defendants as a result of racial discrimination. Another reason lies in poor representation for Black defendants, who are more likely to be low-income and not be able to afford a private lawyer than white defendants. Consequently, Black defendants are often represented in court by public defense lawyers, who are usually overworked, underpaid, and not given adequate time to prepare for trial. Defense has become even more difficult as federal funding has been cut for legal assistance in cases involving the death penalty.

Today, the U.S. criminal justice system continues to hurt communities of color—including us Chinese Americans, but especially our Black neighbors. Recognizing this history helps us understand the past and present failings of policing and prisons—the centuries of racism that drive the current calls for change. Corruption, inequality, and government-sanctioned violence against non-white Americans are far from gone. We Chinese Americans cannot stay silent in this moment, as the sentiment voiced by Man Bun Lee towards injustice against Peter Yew is also what drives the present-day movements—such as Black Lives Matter—to fight the broken U.S. criminal justice system: “We will fight to the end until all our demands are satisfied. We are angry because we are opposed and discriminated against.”

Some clothing collections feel designed only for display, while others feel meant to be worn daily. Vanson Jackets clearly falls into the second category. Their Fixer Upper Colorado Mountain House outfits blend comfort and style in a way that works on any fashion or lifestyle platform.

The history of policing and prisons in America is deeply tied to systemic racism, impacting communities of color, especially Black Americans. From the era of slavery to present-day racial profiling, law enforcement has been complicit in oppression. As we reflect on these injustices, it's important to recognize how far we still need to go. Just like the enduring style of mens winter leather jackets, true justice requires resilience and timeless commitment to change.